The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), formed in 1855, was an international, non-denominational welfare organisation. During the First World War, it quickly established a presence on the Western Front.

Some soldiers wound down and tried to forget the horrors of war by drinking, gambling, or visiting prostitutes. The YMCA aimed to provide the men with what they saw as Christian moral alternatives.

Read this audio story

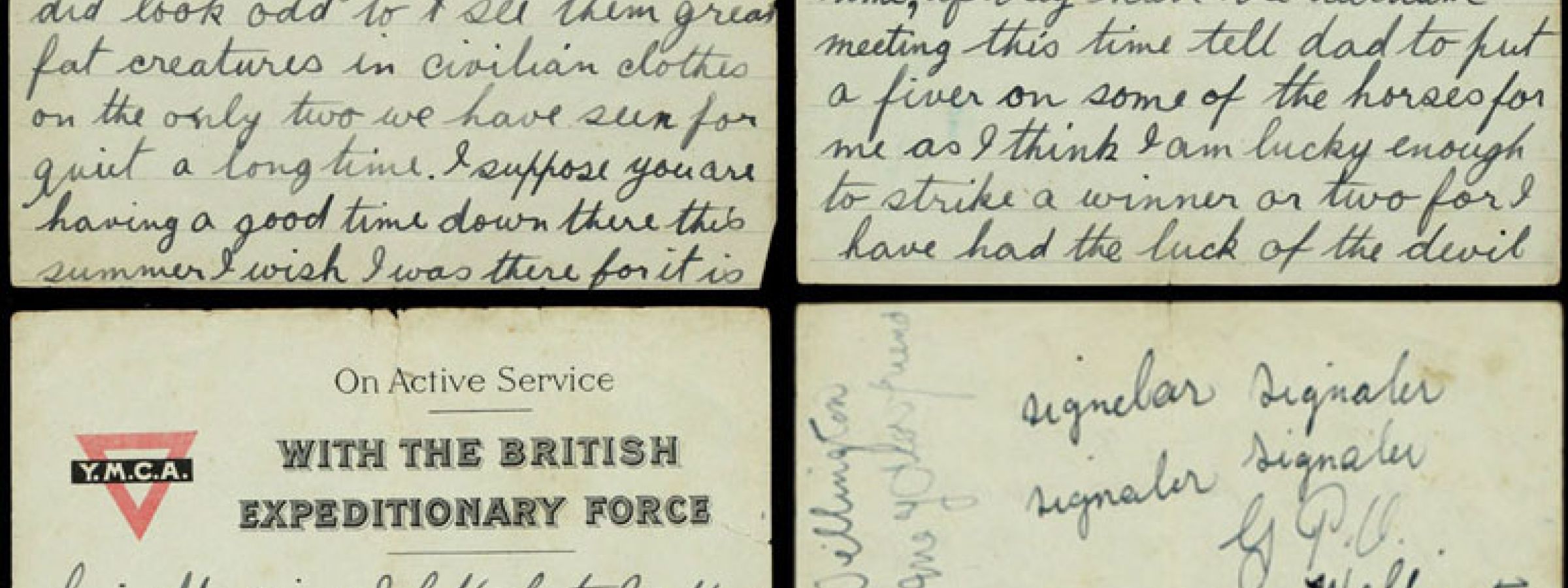

The importance of mail

"Mail was an essential lifeline connecting soldiers with the world they had left behind. Regular contact with home was crucial to morale, it reinforced bonds with loved ones back home, it took soldiers’ minds off current hardships and dangers, and it reminded many of them of what they felt they were fighting to protect. One soldier described letters from home as being like a drink of water to a thirsty person in a desert. Families back in New Zealand equally looked forward to receiving news from soldiers, welcome reassurance that they were okay, at least at the time of writing. New Zealanders were avid letter writers even before the war. In 1914 they sent 110 million letters and 5 million postcards, and because of their simplicity, postcards became even more popular during the war. By January 1917, in just one month, the New Zealand Base Post Office in London received 4,200 mailbags containing 680,000 letters and parcels; 32,000 of these had to be redirected to men who were now in hospitals."

For example, the organisation helped the men stay in touch with loved ones at home through letter-writing. They gave away free pencils, paper and envelopes, and sold stamps, postcards and other stationery items. They also set up comfortable places for the men to read and write letters. This was especially important to the New Zealand soldiers, who were on the opposite side of the world from home, and had no opportunity to visit loved ones when they were on leave. Mail was their only form of contact.

New Zealand Defence Force Library

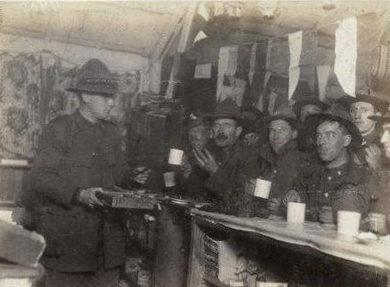

There was much more to the YMCA’s work than this, however. At hospitals and camps, they created entertainment facilities including libraries, cinemas, billiard rooms and non-alcoholic canteens.

They made sure there were ‘wholesome’ activities on offer for men on leave in London and Paris – and in London, they operated a street patrol to try to stop soldiers associating with prostitutes

Closer to the front, they set up ‘YM pozzies’, which advertised themselves with red triangle signs and provided cigarettes, hot drinks, toiletries, stationery, and newspapers. Meanwhile, soldiers leaving the trenches or finishing long marches could get free hot drinks and cigarettes from YMCA roadside stalls called ‘buckshee stunts’. The men especially appreciated cups of tea – a taste of home that wasn’t easy to come by in the French villages.

In 1918, Sergeant Herbert Bellamy wrote that, although he didn’t belong to any church,

‘I am quite convinced that after the war, that as a result of the wonderful work done by the Y.M.C.A. every soldier will have much time for the Y.M.C.A. when they return to New Zealand, and will never forget the Red Triangle people and all that they have done for us in our hour of need.’