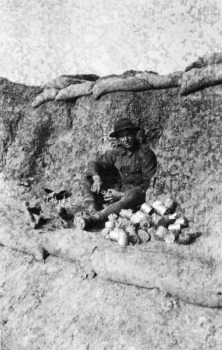

Anzac troops came up with ingenious ways of dealing with equipment shortages and the close proximity of the Ottoman trenches. Hand grenades, or ‘bombs’ as the Anzac soldiers called them, became popular weapons on the peninsula. Because the trenches of the opposing sides were so close, a soldier could easily lob a grenade into an enemy trench without having to leave the cover of his own. While the Ottoman Army was well supplied with grenades, the Anzacs had none, so they had to improvise.

Read this audio story

Alexander Robbin's story

"We were very short of equipment. We didn't have the proper bombs or anything else. We used to make them out of jam tins, and cut up barbed wire and put it in the jam tin, and an explosive. And it had to be lit, the fuse had to be lit with a match or a torch, and that was the type of grenade we used. We didn't have the grenades we had afterwards in the war, where you pull the pin out."

The Anzacs took empty jam tins and packed them with explosives at a small ‘bomb factory’ near Anzac Cove. These bombs were dangerous to make and deploy. Bullets were inserted into the tins along with an explosive charge and anything else they could get their hands on. This included shrapnel, barbed wire and razor blades. These home-made explosives were clumsy and had to be lit by match. ‘It was ... very hard to throw accurately, or any distance,’ wrote New Zealand engineer Charles Saunders, ‘but very effective.’

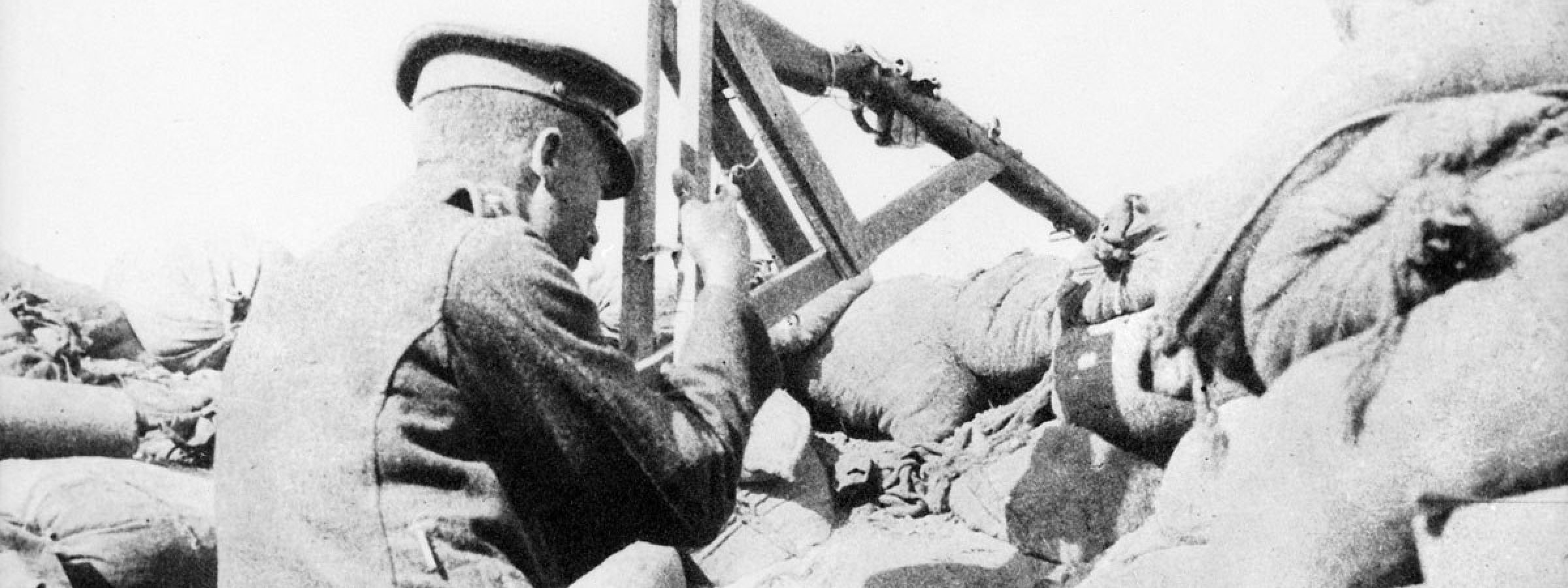

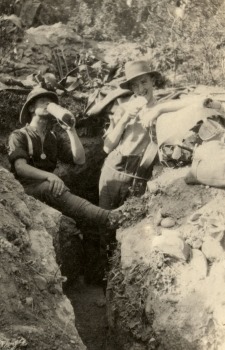

The periscope rifle was first used at Gallipoli in May 1915 by Australian solider Lance Corporal William Beach. Though not as reliable as normal rifles, the periscope meant that the Anzacs could shoot at enemy troops without having to raise their heads above the parapet. Periscope rifles were produced in a makeshift workshop on the beach at Anzac Cove.

The periscope rifle was first used at Gallipoli in May 1915 by Australian solider Lance Corporal William Beach. Though not as reliable as normal rifles, the periscope meant that the Anzacs could shoot at enemy troops without having to raise their heads above the parapet. Periscope rifles were produced in a makeshift workshop on the beach at Anzac Cove.

The upper mirror of the periscope rifle looked along the sights of the gun. The image was reflected down to the lower mirror, into which the soldier, who was safely under cover, peered. Sometimes the periscope rifle was used by a sniper and observer working together. The periscope rifle soon became used in many frontline trenches, in particular Quinn's Post, where the closeness of the Ottoman trenches had made it nearly impossible to fire a shot during daylight.

The majority of New Zealanders on Gallipoli wore the dark green Territorial Force uniforms. As the campaign dragged on into summer, these uniforms could become unbearably hot. Comfort and practicality became more important than regulations and appearance. Soldiers stitched bits of cloth to the back of their peaked ‘forage caps’ for better sun protection, rolled up or cut off shirtsleeves, and turned trousers into shorts. Ormond Burton, a stretcher-bearer at Gallipoli, wrote that ‘slacks were ripped off at the knees and the vogue of shorts commenced. Coats were flung off and then shirts. The ‘Tommy hats’ in which the New Zealanders had landed were soon thrown away and replaced by Australian felts … Within six weeks of landing the fashionable costume had become boots, shorts, identity disk, hat and when circumstances permitted a cheerful smile. The whole was topped off by a most glorious coat of sunburn.’

The majority of New Zealanders on Gallipoli wore the dark green Territorial Force uniforms. As the campaign dragged on into summer, these uniforms could become unbearably hot. Comfort and practicality became more important than regulations and appearance. Soldiers stitched bits of cloth to the back of their peaked ‘forage caps’ for better sun protection, rolled up or cut off shirtsleeves, and turned trousers into shorts. Ormond Burton, a stretcher-bearer at Gallipoli, wrote that ‘slacks were ripped off at the knees and the vogue of shorts commenced. Coats were flung off and then shirts. The ‘Tommy hats’ in which the New Zealanders had landed were soon thrown away and replaced by Australian felts … Within six weeks of landing the fashionable costume had become boots, shorts, identity disk, hat and when circumstances permitted a cheerful smile. The whole was topped off by a most glorious coat of sunburn.’

Images

New Zealand soldier fusing jam tin bombs, Gallipoli, Turkey. Denniston, George Gordon, 1885-1958 :Photograph albums relating to World War I including the Gallipoli campaign. Ref: PA1-o-863-08-4. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22903690

A trench freshly dug on the Apex, Gallipoli (but sheltered from Turkish direct fire). The two occupants consume a meal which includes an Army biscuit. National Army Museum, NZ, 1992.757

Audio

Tpr. Alexander Robbins, 1999.2901-1B, National Army Musuem, NZ.