Wherever the frontline was near to a town, soldiers made the most of their leisure time there. Armentières was particularly close to the fighting. It was just half an hour’s walk away from the rear trenches, and about 10,000 of its 28,000 pre-war inhabitants remained there. When the New Zealand Division first arrived in the town, it was occasionally shelled or bombarded, and civilian casualties were light. However, the attacks gradually increased as the war continued.

The New Zealand men enjoyed this contact with French locals, and the locals in turn welcomed the men and their business. The soldiers used municipal baths, laundries, and brothels. Then there were the estaminets that sprang up – makeshift cafés, usually run by women in homes, farmhouses or cellars.

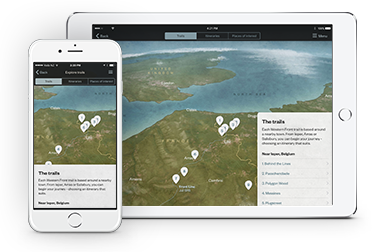

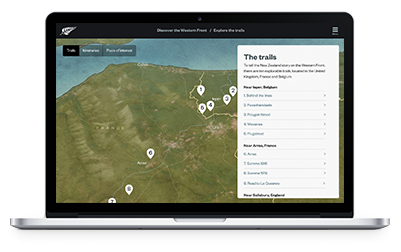

Read this audio story

Leslie Boyd's story

"Armentières was habitated by the local people and there were quite a lot of people living in Armentières while we were there. We got very pally with some of them. I had a very nice girlfriend in Armentières. She was a jolly nice girl and the family were wonderful. There was a mother, a father and Auntie and daughter. They could speak English these people. They just seemed to be doing nothing at the time, they looked after me like a king they used to feed me and look after me and do all the nice things for me."

While some New Zealand soldiers found French and Flemish culture uncomfortably alien, many others enjoyed the opportunity to try new foods and learn a bit of the language.

1998.371 National Army Museum, NZ http://nam.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/8978

New Zealand soldier Cecil Malthus described a stay in Armentières:

A picture theatre and a number of estaminets gave us some pleasant sociable evenings …The Flemish estaminets were very different from our New Zealand bars. Most of them had pianos and provided light meals, chiefly eggs (which were never on the army menu), besides beer and wine….

I soon formed, like everyone else, a great admiration for the girls who ran these places. There were virtually no men left in the town, of course, but the girls needed no protection apart from their own good sense and tact. They were really wonderful – energetic, bright and capable. It was a hard life for them, as they were kept so busy and some of our men were a bit rough, but they more than held their own and had no need of any sympathy...

Leslie Boyd, interview by Jane Tolerton and Nicholas Boyack 17 August 1988, OHInt-0006/61, World War 1 Oral History Archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.