The exact location of the bodies of most of those who died on Chunuk Bair is unknown. In the New Zealand newspapers they were listed as, ‘Reported missing August 8; now believed to have been killed’.

Auckland War Memorial Museum D531.T9 G169 Reserve http://muse.aucklandmuseum.com/databases/LibraryCatalogue/144345.detail

Read this audio story

The failure of the August Offensive

"The August Offensive failed, in my opinion, because the original plan was too complex for the amount of troops available. The August Offensive plan was very complex as well, involving these two columns going up very difficult country in the darkness against opposition. So, to me, that first night was when the campaign failed. Even though the British, as part of the offensive, landed at Suvla Bay, and the Australians and New Zealanders believed they were let down by those British troops who didn’t come immediately to Chunuk Bair and assist them. In fact that wasn’t their orders, but admittedly they showed a lack of initiative in grabbing the high ground in their vicinity, but they weren’t the cause of the failure of the offensive.

"The offensive failed because we didn’t get the positions on that first night and present the Ottomans with a fait accompli. Suddenly the three high points were in Allied hands. Then we could consider whether we could advance across to the Narrows. But even then, I’m not so sure that was a feasible operation, given the lack of our artillery that would have made it difficult to mount an attack. And of course most of the artillery, or the firepower, was on ships, and then firing over the range in positions in advance of the ridge, that was going to be very difficult to coordinate in the absence of radios in those days, so it would have been a very difficult military operation to attack across to the Narrows from Chunuk Bair and Hill 971."

After the Gallipoli campaign, the Ottomans eventually moved away from the area, leaving the bodies of Allied soldiers where they lay. Of the 632 men buried in Chunuk Bair Cemetery, only 10 have headstones. Eight of these 10 are New Zealanders. After the 1918 Armistice, this cemetery was created on the site where the Turks had buried some of the Commonwealth soldiers killed between 6 and 8 August 1915.

Two of the New Zealanders buried in the cemetery are Matthew Persson and Basil Mercer, who both died on 8 August 1915. They were only 17 years old. New recruits were meant to be over 20, but both Persson and Mercer had lied about their age. Private Persson, from Palmerston North, and Private Mercer, from Wellington, are buried next to each other in Chunuk Bair Cemetery.

Read this audio story

Joe Gasparich's story

"I think it was Rhododendron Spur, and there’d been a lot of fighting over this country, right up all that rugged country. And there was scrub covered in all sorts. And there were dead men all over the place.... And they couldn’t get to them. They couldn’t find them, and didn’t dare show themselves in the daytime, and they couldn’t find them at night. They went patrolling all through the places – I went patrolling in some of those places."

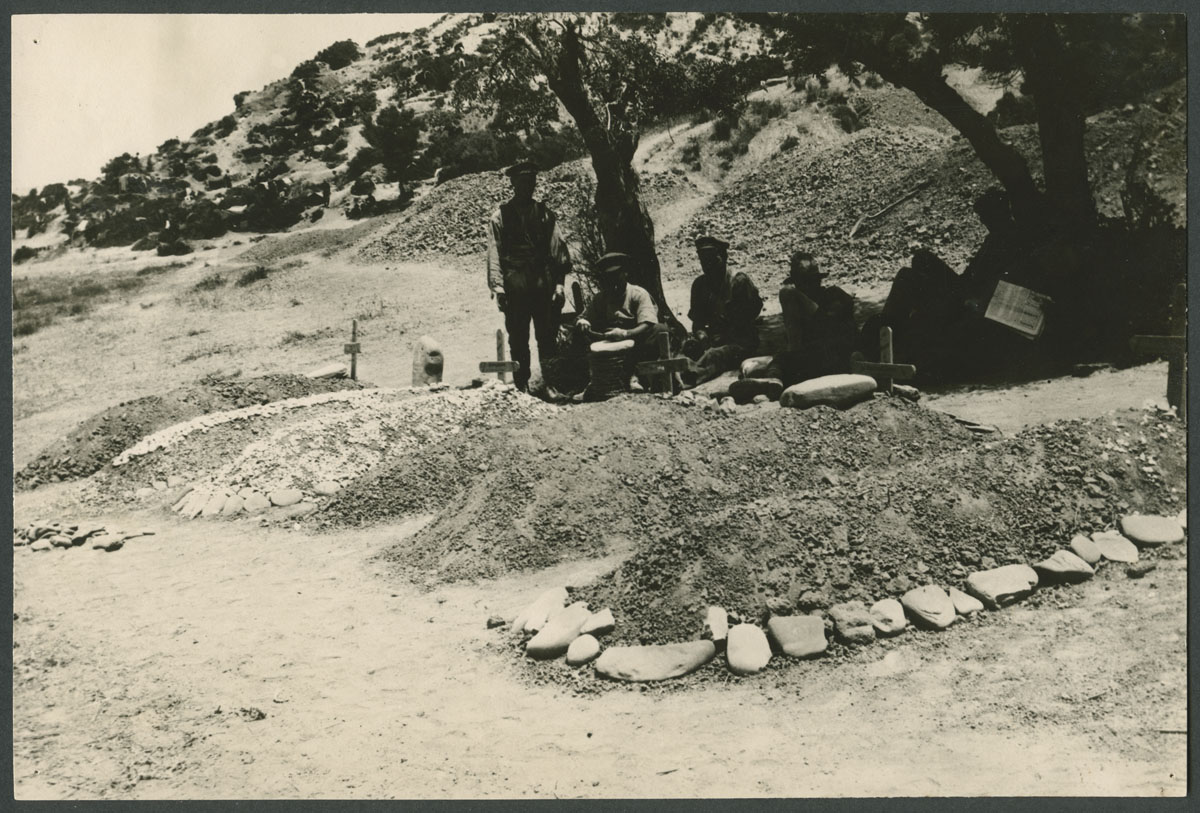

After the evacuation of Gallipoli in December 1915, many dead New Zealand soldiers remained unburied. It was not until December 1918, after the Armistice had been declared, that Allied forces returned to the peninsula.

The Canterbury Mounted Rifles were part of an Allied occupation force that helped monitor Ottoman compliance with the Armistice. This gave them the opportunity to revisit the old Anzac battle sites,where the Graves Registration Unit was working. Special parties searched for graves and bodies of New Zealand soldiers. Graves were identified and cleared, skeletons were identified and bones collected for burial.

The Canterbury Mounted Rifles were part of an Allied occupation force that helped monitor Ottoman compliance with the Armistice. This gave them the opportunity to revisit the old Anzac battle sites,where the Graves Registration Unit was working. Special parties searched for graves and bodies of New Zealand soldiers. Graves were identified and cleared, skeletons were identified and bones collected for burial.

Though it was difficult work, an observer at the scene in December 1918, Ernest Peacock, was greatly impressed with what he saw from the soldiers. ‘Going over each remnant, buttons and scraps of cloth and other details,’ wrote Peacock, ‘they found sufficient to be convinced that the remains were those of a comrade. It is impossible to describe or to do justice to the tender, reverent care with which each particle was gathered together, a grave dug, and the whole buried in quite impressive solemnity. There was no funeral service but no dignitary ever received a more truly loving Christian burial than did those remains.’

Inline Image:

A carved stone commemorating the dead from the 1st (Canterbury Yeomanry Cavalry) Squadron of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment killed in the August Offensive on the first day 6 August 1915. National Army Museum, NZ 1993.1203 http://nam.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/6585

Audio:

Sgt Joe Gasparich, 1999.2935-1B, National Army Museum, NZ.