New Zealand had no airforce of its own, so its aviators generally joined the British Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Naval Air Service or, from April 1918, the Royal Air Force. Some went to Gallipoli, but most were active at the Western Front.

Governments invested large amounts of money and effort into aviation during the First World War, and globally the technology progressed by leaps and bounds.

At first planes were used only for reconnaissance and photography, and when fighter planes were first developed, their purpose was simply to shoot down enemy reconnaissance aircraft. However, their role soon expanded. In the later battles of 1917, particularly at Cambrai in November, both sides used planes to support soldiers on the ground, by flying low and shooting.

Read this audio story

Stanley Herbert's story

"Once a German plane come over, course we could tell the German planes from the English planes just like that, they had a different sound altogether. They were terrific to see a German plane come over didn't matter what height they'd shoot him down just like that. I saw many many planes shot down, hit, perhaps you'd see the pilot coming down, perhaps he wouldn't perhaps he'd be in the..and the plane would just smash down on the...but that was just a matter of course."

Early in 1917, the German Imperial Air Service was clearly superior, in terms of both technology and tactics. One effective new German tactic involved groups of specialist fighter planes, known as Jastas, flying in attack formation.

However, it was the battle of Arras in April 1917 that brought home to the British how far behind they were slipping. They made significant gains on the ground, but their air assault was a failure. They suffered four times the Germans’ losses, despite having twice as many aircraft. (Three New Zealanders – John Cock, George Masters and Melville White – were amongst the casualties.)

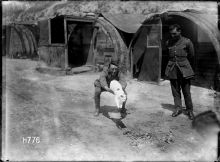

Courtesy of Mr Clive E. Collett, Auckland War Memorial Museum - Tāmaki Paenga Hira

‘Bloody April’, as it became known, forced the British to make improvements in air training, policy, technology and tactics. Within a few months, they had introduced improved aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory SE.5a, Sopwith Camel, and the revised Bristol F.2b Fighter.

From then on, they went from strength to strength. At the start of the war, British air services contained 2,000 men, working with 200 aircraft that would seem primitive by later standards. By the armistice, there were nearly 300,000 men in their airforce, flying 22,000 state-of-the-art planes.