Sling Camp

You’re standing next to the famous ‘Kiwi’ - that looks down on Bulford Camp, at the part, that was once known as Sling Camp. The kiwi was carved into the chalk here in 1919, after the war, by New Zealand troops, who just wanted, above all, to go home. Officers at the camp needed to find something, anything, to keep the men busy, so the idea of the kiwi was conceived. It definitely would have kept the men busy, because from the kiwi’s feet to the top of its back - is around 130 metres high.

In 1914 Sling Camp was set up as part of a much larger British camp at Bulford to train the New Zealand volunteers who became the British section of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. New Zealand, by 1916, had developed perhaps one of the most efficient reinforcement systems in the world. It had to be efficient, because shipping was scarce and so unlike Australia and Canada who took new recruits through the door as they came in, New Zealand needed a different system. A New Zealand volunteer would front up to the recruiting hall and after he was signed-up, he was then sent home again to be called-up in monthly batches of 2,000, to report for initial training at Trentham. He would then go for advanced training at Featherston Camp, before marching back over the Rimutakas then being sent on final leave before going overseas. It was an efficient system.

If you had previous territorial force experience, your training was accelerated, but if you were not fit enough or could not shoot you were put back to a later reinforcement draft, so that by the time you left New Zealand you had completed your musketry training, you were fit, and you’d marched over the Rimutakas - a rite of passage for all recruits.

These green soldiers then had this six or seven week voyage to the United Kingdom, arriving at Liverpool or Southampton, and they were then taken by rail to their training depot. Infantry were trained at Sling, with the Rifle Brigade at Brocton. The machine gunners were trained at Grantham, and there were separate engineer and artillery depots, with the engineers and Pioneers at Boscombe and artillery at Ewshot.

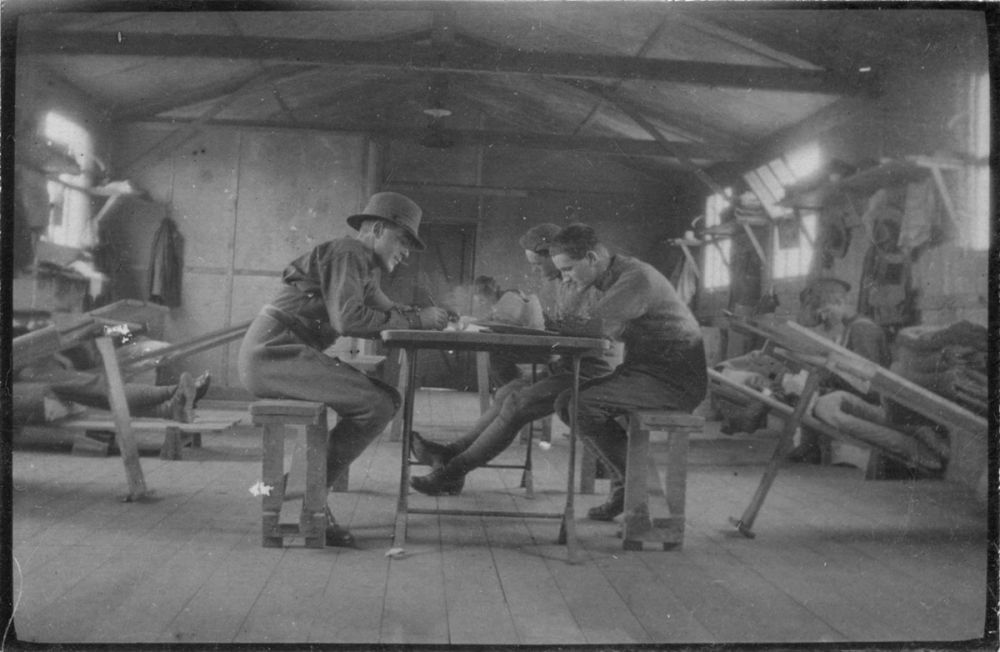

As warfare evolved, the techniques and training also had to change to keep pace. Men were introduced to new weaponry and technology, and they had to learn about the equipment in detail. This included the Lee Enfield Rifle, grenades, mortars and the Lewis light machine gun.

As the war progressed, the way armies fought changed as well. At first it was the techniques of open warfare that were taught, then it settled into trench warfare, and then - back to open warfare again, but now it evolved into a highly-mobile open warfare, with machine guns, artillery, tanks, aeroplanes, gas and flamethrowers. Teams of men were trained to fight in small groups, employing assault tactics to destroy enemy machine guns nests - one by one. All this training happened at Sling.

A New Zealand soldier could spend eight to ten months in the training process, going from New Zealand to England, then on to France or Belgium, before getting to the front - but it was a regular and sustained process.

James Allen, the Minister of Defence, was responsible for the organisation of New Zealand military forces during the war and he was instrumental in introducing conscription in 1916. Allen fought hard to keep the size of the New Zealand force to a division, and he recognised that the small, specialist pool in New Zealand could easily be wiped out if everyone volunteered at once. You simply couldn’t have, for example, all of the Otago Medical School enlisting as stretcher bearers as they did for the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915. Training them to be doctors was more important and so they were sent back from Egypt to continue their medical training.

In 1917, an extra infantry brigade was raised, but this was reduced again in 1918. Allen carefully measured what the country could sustain, and even then the tragic cost of this war meant that New Zealand, of all the Dominions in the British Empire, still sent the highest percentage - nine percent - of her population to the war.

This was 100,000 men out of 240,000 men of eligible age. There were close to 60,000 casualties, including 18,000 dead.

Below where we stand at the Kiwi were the New Zealand barracks at Sling Camp. In 1919, with the armistice signed and the war over. This emblem was carved to keep bored men busy before they could be sent home. It is now a reminder of the thousands of New Zealanders who passed through here on the way to the Western Front.