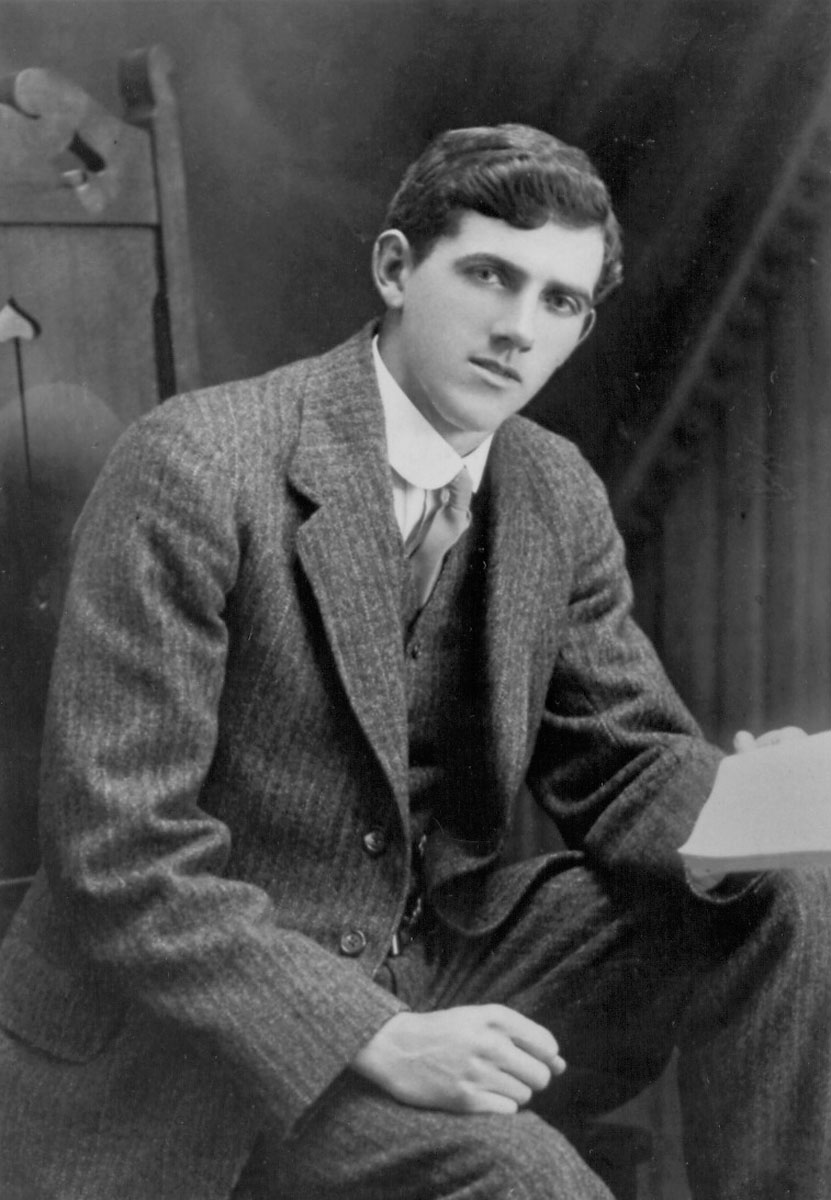

Private Cecil Malthus

Canterbury Infantry Battalion

Quinn’s Post was a far cry from the Nelson classroom where Malthus had once taught. He didn’t shy away from describing the horrors of war – but also praised the grit and generosity of his fellow soldiers.

Read this audio story

Cecil Malthus

Private Cecil Malthus was a Nelson schoolteacher who served in the Canterbury Infantry Battalion at Gallipoli. While there, he did three stints at Quinn’s Post. His letters and diaries provide a fascinating insight into the period New Zealanders fought there.

Quinn's Post was reached by a long straight staircase too steep for mules, and all the stores had to be carried up by hand. To men stricken with dysentery, the daily water and stores fatigue was a cruel task.

When the New Zealand Infantry Brigade assumed responsibility for Quinn’s Post in late May, it had been held by the Australians since they landed on 25 April 1915.

The retention of Quinn’s Post had been perhaps the most magnificent of the many great achievements of the Australians. It appeared to us when we took over that the desperate nature of the fighting must have prevented the Australians from making any elaborate system of fortifications, and that they had only maintained a bare existence from day to day, so that when we arrived there we found the trenches still in a primitive state.

Quinn’s Post was a precarious and dangerous spot with a high rate of casualties.

The Turkish bombing was incessant and terribly effective, and their rifle fire was deadly. To look over the parapet was suicide, and even a periscope would be shattered if held a moment too long.

A feature of Quinn’s Post was the close proximity of the Anzac and Ottoman trenches – at some places only two or three metres apart.

The Turkish trenches were only seven yards away, and at one point we had a listening post just six feet from their line. One could step out through a gap in the sandbags and touch the Turkish parapet – but one was much better advised not to.

With the enemy so close, life at Quinn’s Post was extremely stressful.

Our first 24 hours in the front line, though considered about normal, resulted in ten casualties out of 80 men. I remember a Timaru acquaintance who landed with a batch of reinforcements, came straight up into the line, and was out again in half an hour with an arm blown off.

As the campaign progressed into the hot summer, flies became an enormous nuisance.

The heat of the sun caused a plague of flies which bred and fed on the dead bodies, the latrines and the refuse of food, and which contaminated everything we ate. They would chase the food into our very mouths.

Malthus also witnessed the terrible psychological effects of the Gallipoli conflict.

I remember in particular a slightly wounded man who ran out streaming with blood and roaring at the top of his voice. He was badly shell-shocked, and he had to be transferred to the ambulance corps down at the beach, where he lasted another couple of months.

After his first stint at Quinn’s Post ended, Malthus rested, and then returned for another spell. He was impressed with what he saw.

Returning on 17 June we found the post so completely transformed that it was now comparatively comfortable and quite a good defensive position. All these improvements were due to the energy of Colonel Malone of the Wellington Battalion.

But as the hot summer continued, life became incredibly difficult.

Every day the sick parade increased, and men were sent away down in dozens to the hospital ships. Of those who remained, nearly all were weakened and suffering.

Yet despite the unbearable conditions, Malthus was impressed with his comrades.

Generosity, good fellowship and cheerful acceptance of every hardship and danger. That is my abiding impression of our two months at Quinn's Post.

After the Gallipoli campaign, Malthus served on the Western Front, where he was injured in September 1916. He returned to New Zealand six months later. Malthus died in 1976.