New Zealand Memorial

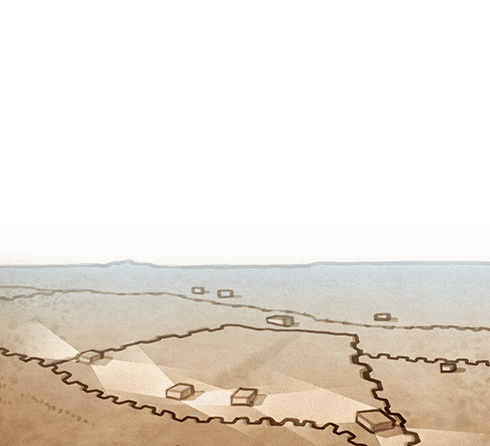

You are in the New Zealand Memorial Park at Messines. Behind you is the New Zealand Battle Memorial - which commemorates the actions of the soldiers who took part in the battle of Messines from 7 to 14 June 1917. Looking out over the valley, you are facing in the direction of where the New Zealand soldiers were assembled - ready to attack.

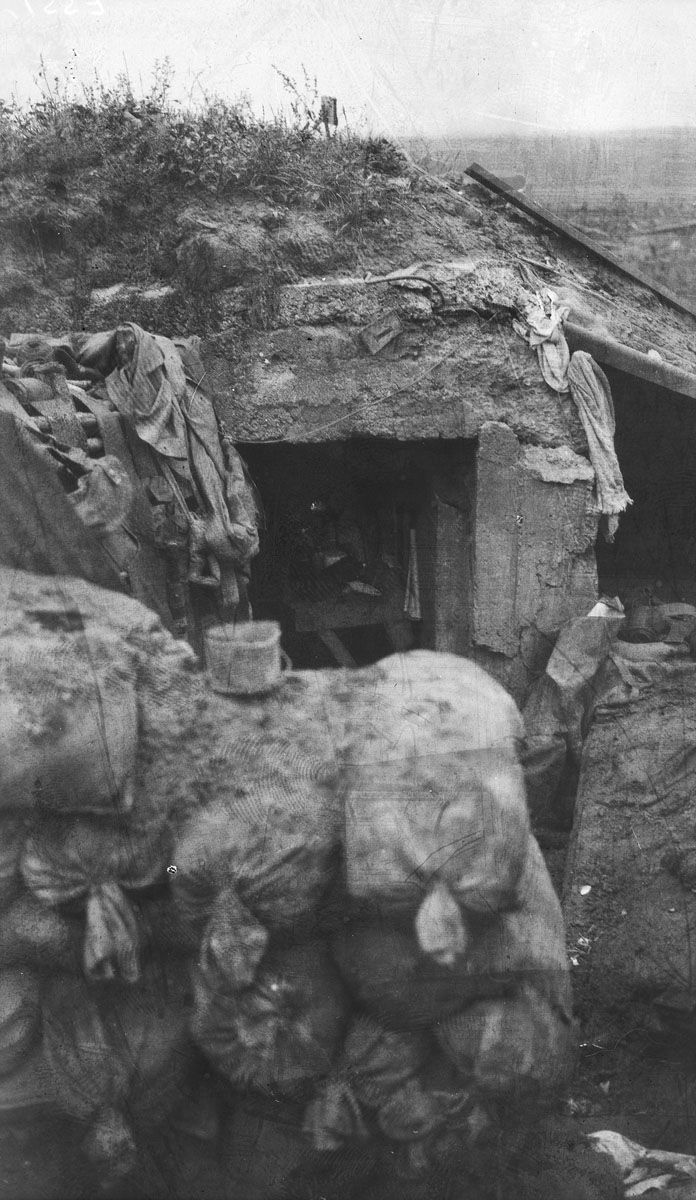

To your left and right, you can see the remains of two German bunkers, which were part of an enormously strong complex covering this entire ridge. The Germans had developed new technology for their defences and constructed concrete bunkers reinforced with steel - capable of withstanding artillery bombardments.

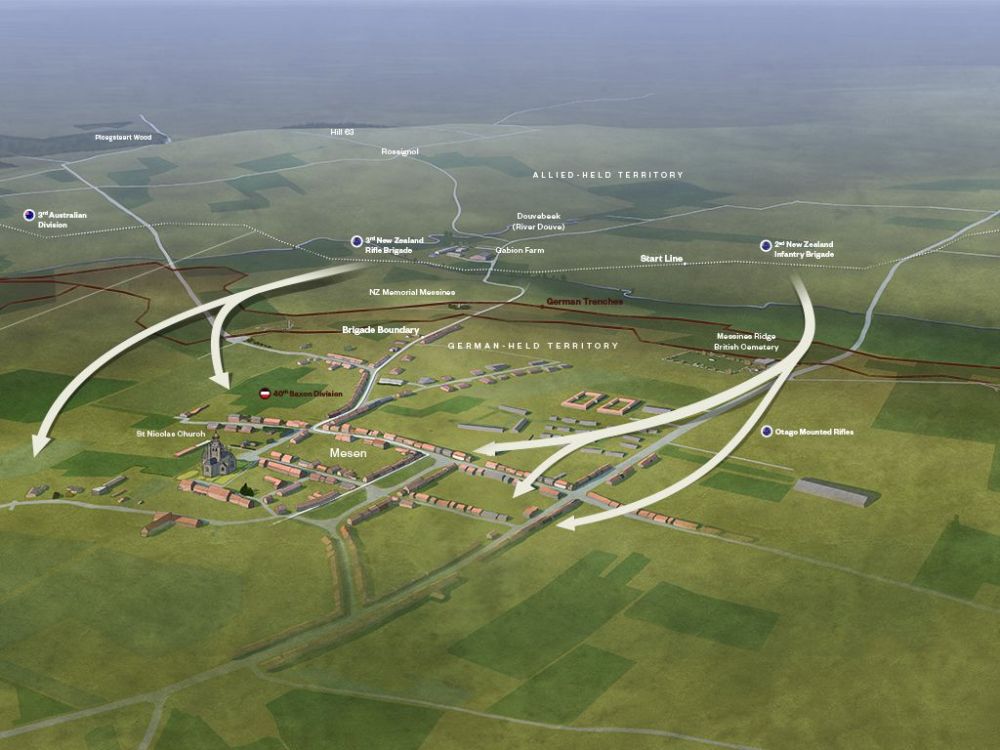

This was sought after high ground - and what you are standing on was the Uhlan Trench - the German front line, and it stretched all the way up to Wijtschate, which you can see in the distance on your right. Looking back over the valley, to your left on the skyline you can see two spires, which is Armentieres. Following the skyline to the right you come to some higher ground in front of you – this is Hill 63 and behind that is Ploegsteert Wood - or ‘Plugstreet’ as it was known. This was the area that the New Zealand Division occupied.

Gabion Farm is the farm house immediately below you in the valley, and in front of it you can just see the river Douve marked by the willows. The New Zealand startline was on the other side of that stream.

Messines is possibly best known for the monstrous mine explosions detonated by the British at zero hour, on the morning of 7 June. These 19 mines, packed with tonnes of explosive and placed under the German lines were the result of two years of careful and dangerous tunnelling, by many experienced Allied miners. The preparation for this assault on the ridge had been intense, and life on both sides of the lines had become a test of endurance.

“Every man in the Division had to spend his nights working, and getting what sleep he could during the day. This in itself was a severe tax on the men’s endurance… with the enormous concentration of artillery, life on the slopes in front of us had become practically impossible.”

Major-General Russell

The mines were detonated at 3.10 in the morning, causing massive eruptions, destroying the enemy trenches, killing hundreds of German soldiers instantly and burying many others alive.

“On the left a great mine went up in vast masses of earth and smoke and lurid red flame like a night eruption from the throat of some great volcano. It was the great momentary flash of the red flame, like the red of a blood orange brilliant against the black smoke, that impressed the vision. In quick succession other mines, five or six in number, heaved themselves skyward with awesome effect, making the ground quiver as if stricken with a great earthquake.”

Captain Malcolm Ross

The tremors from these huge explosions were reportedly felt as far away as London and Paris. One of the craters formed was 12 metres deep and over 75 metres in diameter. On the evening before the attack General Plumer commented to his staff: “We may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography.”

This meticulously planned attack was the first part of Field Marshal Haig’s master plan to break out of the Ypres Salient in Belgium - which was surrounded by Germans on three sides. Messines was the first objective, pushing the Germans back from the Messines ridge to the south was key to eventually clearing the enemy from all the ridges surrounding Ypres.

For the New Zealanders, and all the other eight attacking divisions the explosions of the mines signalled the beginning of the assault. As soon as these earth-shattering detonations went off, soldiers clambered out of their trenches to attack, protected by a carefully-timed creeping artillery barrage that rained hell down on the surviving German defenders. The German bunkers here overlooked the New Zealand advance - which came up either side of the road in front of you - leading up to the village of Messines. Here where you stand was their first objective.

As the New Zealanders advanced, the Germans here, were still reeling from the mine explosions and the shelling, and they barely had time to set up their machine guns before the New Zealanders were upon them. Dozens of Germans immediately surrendered, those who didn’t were shot down or grenaded inside their bunkers.

“The German first line simply didn’t exist except for a few very strong concrete dugouts which were treated to a well timed bomb. The second line was much the same and most of the chaps settled the first Hun they saw, either with a bullet or bayonet to make sure of having at least one to their credit.”

Sergeant Joseph Cody

Small teams of men led by their section commanders and platoon sergeants, moved forward, attacking each bunker, armed with Lewis guns and Mills bombs, some providing suppressing fire while the rest of the team would skirt the bunker’s flanks and throw bombs into the rear entrance. Once these initial positions had been taken, the New Zealanders continued forward, behind you, into the town of Messines.

General Russell, the New Zealand commander, intended for each brigade to bypass the town and then the selected follow-up groups were to clear the remaining defenders from the ruins. The attacking groups were strictly limited in number so they could shelter in the cellars to protect them from the imminent German counter-bombardment. It was not yet dawn, and the New Zealanders pushed through, mopping up the disorganised and startled enemy. The Germans however, soon regrouped, and fought back, sniping and hurling grenades from the ruins of the city.

This is where Corporal Samuel Frickleton of the 3rd Rifle Battalion distinguished himself as part of the spearhead assault force, running forward through the British artillery barrage and taking out two machine guns that were holding up the advance. For his actions Frickleton received the Victoria Cross - the only man to receive this award during the fighting, despite three others being nominated.

Meanwhile, the left flank of the New Zealanders advanced, to the right of the road in front of you, and engineers and the Cyclist Battalion cleared the way for the Otago Mounted Rifles to come forward with their horses to recce the remaining German positions over the ridge. They charged forward but were met by long-range German machine guns and more wire. It was one of the few attempts at mounted action during 1917. The Germans had been pushed back off the ridge and fell back.

Messines was regarded by Haig as his most outstanding success in the war to date. Its success was due to careful planning; two years of skillful mining, detailed rehearsals for the infantry attack, a massive preparatory artillery bombardment, a well-timed artillery barrage, excellent leadership at all levels and the determined advance by Allied troops, with each division performing well.

But every battle has its cost, and at Messines, the New Zealanders suffered with 3,700 casualties including 700 dead. Most of the casualties were inflicted during the German bombardment that followed the capture of the ridge. Despite the casualties, New Zealand was fast earning a reputation as a fine fighting division with an impressive commander, Russell.