One of the most difficult issues faced during the August 1915 offensive at Gallipoli was communication. The Divisional Signal Company for the New Zealand and Australian Division had a shortage of operators and officers, many of whom were evacuated sick or wounded.

Installing and maintaining the communication circuits and telephone and telegraph lines was difficult because of the rough and scrubby Gallipoli terrain, as well as constant enemy fire. Service often suffered due to the breakdown and congestion of lines. Maintaining communications was one of the major challenges during the advance up to Chunuk Bair.

Installing and maintaining the communication circuits and telephone and telegraph lines was difficult because of the rough and scrubby Gallipoli terrain, as well as constant enemy fire. Service often suffered due to the breakdown and congestion of lines. Maintaining communications was one of the major challenges during the advance up to Chunuk Bair.

Sapper J. W. Maxwell of the Divisional Signal Company described the job of a signaller. ‘Each man on this duty carries on his back a portable telephone, which is attached, at intervals, to the wires. The linesman knows that if his call from the portable telephone is not answered from the signal office there is a break in the wire between him and the office, and so he is able to locate the break.’

Communication was particularly important at night, when units could not see each other in the dark. Units constantly lost touch with each other and their headquarters during the night advance through the foothills below the Sari Bair Range. Many breaks in the lines were caused by shrapnel fire. Communications were to blame for much of the confusion that occurred around the attack on Chunuk Bair.

Communication was particularly important at night, when units could not see each other in the dark. Units constantly lost touch with each other and their headquarters during the night advance through the foothills below the Sari Bair Range. Many breaks in the lines were caused by shrapnel fire. Communications were to blame for much of the confusion that occurred around the attack on Chunuk Bair.

On the summit of Chunuk Bair the portable field telephone was the only instant form of communication available to Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone, commander of the Wellington Battalion. If the telephone failed, his only alternative was to send runners back and forth to deliver messages. This could take the runners hours, assuming they made it back safely at all.

Portable field telephones were heavy, weighing around 2.5 kilograms, and required connecting to a central switchboard, via a copper wire and rubber-insulated cable. The signal parties not only had to operate and carry the heavy phones up to the summit of Chunuk Bair, but also had to roll out and join the lines of cable needed to connect it.

Read this audio story

Cyril Bassett's story

"I went on and followed the wire all the way across the crest we’d come across. It was a scrubby place – not much shelter. I’d come across three breaks; I mended two of them, they were pretty close together. Followed the wire on a bit further and mended that. I don’t mind telling you I was pretty [?] while I did, with the stuff that was coming across. Luckily there wasn’t much shrapnel. Bursts every now and again, but there was a lot of rifle and machine gun fire, mainly from the left. Well, time was getting on then and when I reported back to headquarters fairly late in the afternoon, found the wire had gone again. So that night we decided, Bert and I, Bert in the meantime had come back quite safe. He’d straightened up the wires on his way back, and he and I went out that night and laddered all the lines. It was a pretty exhausting sort of a job. The fifth reinforcements had arrived by this time and they were lost. A lot of our time was spent in guiding these chaps up to the line. And of course you can imagine what the position was between the line and the hill…"

During the battle, the signallers established a telephone line with Malone’s headquarters on Chunuk Bair. However, they struggled to keep it working as the unburied line was continually damaged by Turkish fire. The signallers constantly exposed themselves to danger as they tried to either repair the lines or relay messages on foot. You can listen to a story about signaller Cyril Bassett in the Stories & Insights section of the Chunuk Bair trail.

Images

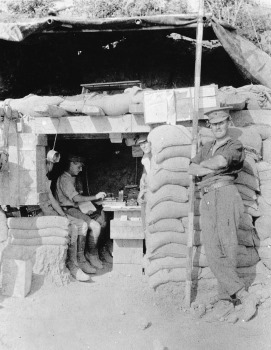

Headquarters Signals at ANZAC Cove, Gallipoli, Turkey. Powles family :Photographs. Ref: PA1-o-811-14-2. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23087779

4/346 Sapper Stephen Francis Newcome Weymouth, New Zealand Field Engineers (later Lieutenant) and 9/430 Trooper Leonard Stuart Watson, Otago Mounted Rifles share a pipe in a dugout at the Signalling Station on No 2 Outpost, Gallipoli. Trooper Watson wears the single ear piece connected to an early Fuller Phone which could only send messages by morse code. National Army Museum 1991.884 http://nam.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/2903ling apparatus.

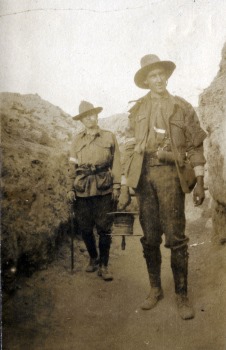

Main sap frm Anzac Cove. Shows two soldiers in a deep cutting. One holds a reel of wire, probably for field telephones. This is probably the deep communication trench (sap) dug in preparation for the August offensive, leading north from Anzac Cove. Wairarapa Archive

Audio

Cyril Bassett, National Army Museum, NZ.