As soon as mining was in use at the Western Front, so was counter-mining – because the only way to destroy an enemy tunnel was by using another tunnel. Eventually, it was almost as if a second war was being waged underground.

When the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company (NZETC) arrived in France in March 1916, they were immediately tasked with counter-mining at the foot of Vimy Ridge, near Arras. It was stressful work, as the men never knew whether the enemy might have detected them. Other dangers included cave-ins and toxic gas, and in fact, 75% of the NZETC’s mining casualties were from carbon monoxide poisoning.

© Imperial War Museums (E(AUS) 1683)

In September 1916, an NZETC scout discovered several medieval underground quarries and cellars at Arras. The British Third Army decided to use these to house a powerful force of troops that could eventually reach and break the German frontline, one kilometre east of Arras.

The NZETC played a prominent part in digging the massive network of tunnels that would link together the old quarries and cellars, make them habitable and extend them.

The men worked on two connected systems: Saint-Saveur (which the British began) and Ronville (which the New Zealanders dug entirely on their own). The tunnellers challenged themselves to see how far they could dig in a day, constantly trying to beat the previous day’s work.

Read this audio story

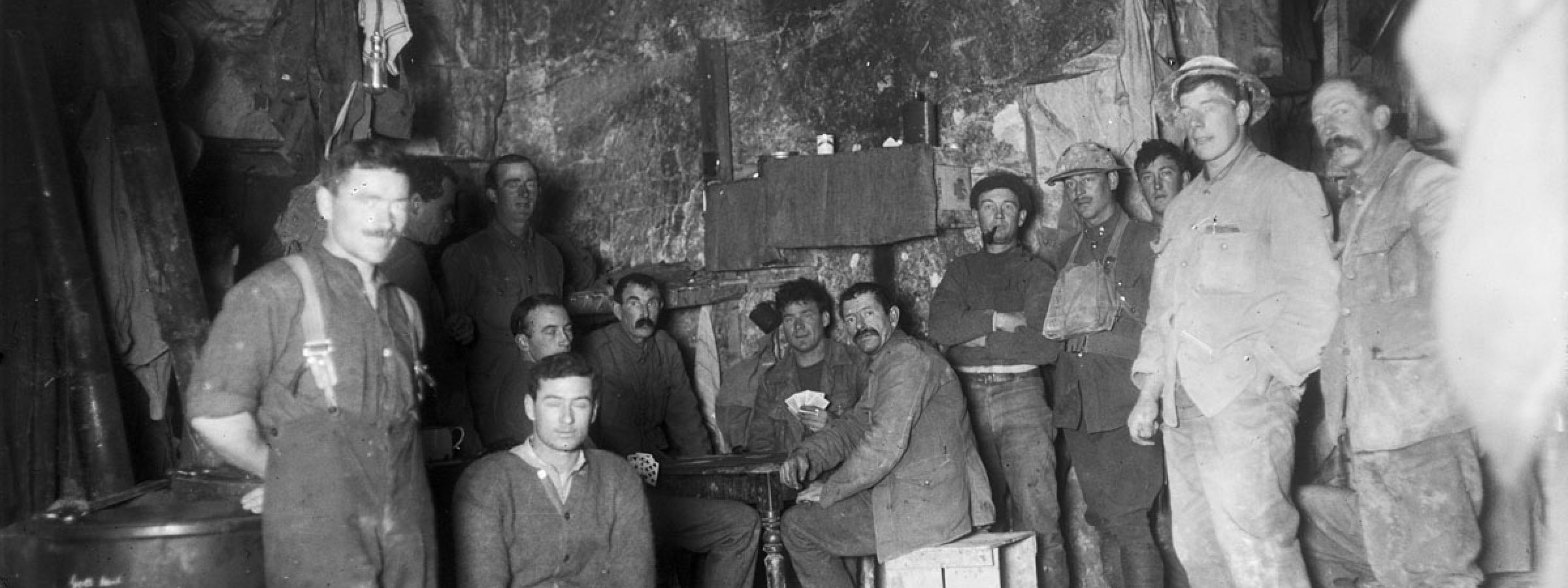

Life underground

"During operations at Arras in 1916 and 1917 New Zealand tunnellers experienced several very different underground environments. Initially they were involved in the underground war. They dug shafts, listened for the enemy and placed camouflets to blow in his tunnels. Working in the narrow tunnels in damp, fetid air, the tunnellers had many nerve-wracking moments as they sought to forestall their enemy counterparts when they were heard approaching. Over the winter the tunnellers also worked on the cavern system under the city, helping to create facilities to house up to 20,000 men. This was a much less trying environment. The caverns were spacious, the air was good and the threat from enemy action was limited. In both environments the tunnellers’ underground activities were confined to their shifts as they lived above ground in billets elsewhere."

By April the following year, the New Zealanders had built and made safe a vast network of underground galleries, halls, dormitories, kitchens, offices and hospitals, so that they were able to house at least 12,000 men. They installed electricity, water and sewerage, and dug further tunnels that led directly outwards from these cavernous spaces, straight to key German positions. Completed, the two systems each involved over 2,000 metres of new tunnel.

To help everyone find their way around, the NZETC gave New Zealand names to places in the Ronville system: the northernmost point was Russell, the southernmost, Bluff. They gave British names to places in Saint-Saveur, and linked the two systems with ‘Godley Avenue’, named for General Godley, the New Zealand Expeditionary Force commander.

On 9 April 1917, the tunnel exits were blown in no-man’s-land, and men poured out. The Battle of Arras had begun.