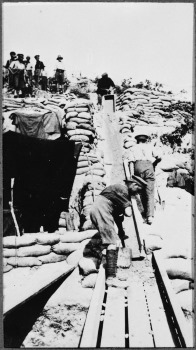

War at Gallipoli was not just waged above ground, but also underground. From May 1915, both sides engaged in mining around posts held by Anzac troops on Second Ridge and at the Nek.

The mine warfare at Quinn’s Post began with listening tunnels. When the Anzacs realised that the Ottomans were tunnelling towards the post, several enemy shafts were destroyed. However, they missed one and it was exploded near part of Quinn’s Post. After the ensuing fighting subsided, a major effort was made to build a protective apron of tunnels in front of Quinn’s Post.

According to the Official History of the New Zealand Engineers, ‘Several small mine tunnels had been pushed out by the sappers in front of Quinn's during May, with a view to protective rather than offensive action, since it was recognised that a Turkish mine of any magnitude would have practically had the effect of blowing the top clean off the small crest of the ridge held by our men.’

According to the Official History of the New Zealand Engineers, ‘Several small mine tunnels had been pushed out by the sappers in front of Quinn's during May, with a view to protective rather than offensive action, since it was recognised that a Turkish mine of any magnitude would have practically had the effect of blowing the top clean off the small crest of the ridge held by our men.’

Private Cecil Malthus of the Canterbury Infantry Battalion served at Quinn’s Post and wrote that it was to ‘meet and counteract this [Turkish] danger that our own miners were so busily employed.’ Although this mining was mainly a defensive move, Malthus admitted that ‘it also meant that our miners could at any time blow up any required part of the enemy’s front line, and several times they did so.’

Volunteers with mining experience were drafted from infantry battalions and formed into tunnelling gangs. Similar action was taken at Courtney’s, Pope’s and the Nek. ‘I called for over one hundred volunteer miners,’ wrote Lieutenant Henry Clark of the New Zealand Engineers in a letter to his father, ‘and the call was heartily responded to.’ Underground warfare was extremely dangerous. ‘There is something about underground warfare that is at once interesting and exciting’, wrote Clark, ‘one never knows for one minute to another when he may be blown up or buried alive.’

Read this audio story

Vic Nicholson's story

"Most of the garrison at any time in Quinn's Post got mixed up in the mining in the mining galleries. That was constituting and making the galleries, and it was left over a lot to the infantryman, who could work when he was off duty at night. And it didn't matter very much whether it was night or day because it was always night down there. And the galleries ran from our line out as near as we could get to under the Turkish line. And to be pushed along one of those galleries on the working face and chipping away with the little entrenching tool, and filling a sandbag, scraping the spoil into a sandbag and passing it back against a line of other blokes who were filling up the tunnel was not very bright. It was more of a frightening experience than anything else, especially if you did happen to hear."

Mining posed dangers for soldiers above ground, too. At Quinn’s Post, the sounds of enemy miners under the ground could often be heard. And there was the ever-present danger that an Ottoman mine deposited by a tunneller could explode beneath your feet. ‘Suddenly I heard a terrific roar,’ wrote Henry Clark about an attack at Quinn’s Post in late May, ‘saw a great flash, and then a hail of earth and stones descended on my head. The enemy had exploded their mine.’

Mining posed dangers for soldiers above ground, too. At Quinn’s Post, the sounds of enemy miners under the ground could often be heard. And there was the ever-present danger that an Ottoman mine deposited by a tunneller could explode beneath your feet. ‘Suddenly I heard a terrific roar,’ wrote Henry Clark about an attack at Quinn’s Post in late May, ‘saw a great flash, and then a hail of earth and stones descended on my head. The enemy had exploded their mine.’

Mining was hard work. ‘We knew our jobs and worked like Trojans,’ wrote Australian Corporal Hedley Howe, who was in a mining gang at Quinn’s Post. ‘Each gang was expected to drive twelve feet (about 4 metres) in an eight-hour shift... It was the hardest labour on the peninsula.’ The tunnels were often tiny – only about 2 metres high and less than a metre wide. The men had to dig them by hand, as explosives were not permitted.

As each side tunnelled towards the other’s line, they would sometimes get very close to each other. ‘I have repeatedly discovered the enemy mining very close to us,’ wrote Henry Clark, ‘and on three occasions have blown in their galleries.’ Sometimes the opposing players in the ‘underground drama’ would meet and fight it out. At Courtney’s Post, Sergeant Horace Newman, of the New Zealand Engineers, used his bayonet to enlarge a hole between an Anzac and Ottoman tunnel, and then entered the enemy tunnel. However, an attempt to lay a charge attracted the enemy’s attention. ‘Newman shot one of them and held up the others while the hole was blocked with sandbags,’ reports the Official History of the New Zealand Engineers. Then ‘the charge was laid behind the block and blown with disastrous results to the enemy's mine.’

Images

Mining at Quinn's Post, Gallipoli. Hampton, W A, fl 1915 :Photograph album relating to World War I. Ref: 1/2-168806-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22857890

A soldier from the 10th Infantry Battalion in a tunnel trench at Silt Spur. Shafts of light beam into the tunnel from firing positions (right), while on the same side bombing tunnels lead off from the main corridor. Australian War Memorial P02321.026 http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P02321.026/

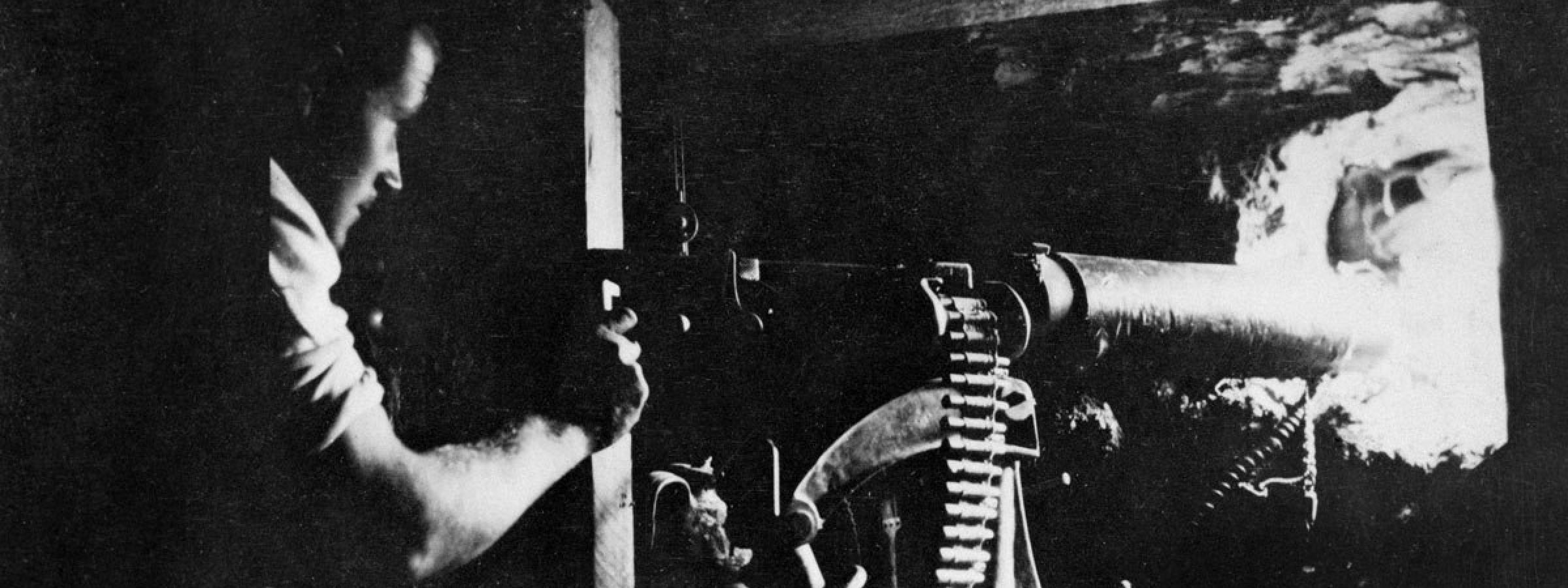

An Australian soldier firing a Vickers .303 machine gun on Turkish positions. Lit by sunlight through the observation hole at right, the post one of many in the extensive array of tunnels connecting the Australian front line positions. Australian War Memorial P08137.003 http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P08137.003/

Audio

Pte Vic Nicholson, 1999-2999-1A, National Army Museum, NZ.